FastHTML is one my favorite things happening in the web world right now. If you haven't seen it before, it's powered by what are called "fast tags"; implementations of every HTML tag as Python functions. Since we can pass python strings as arguments into fast tags, we can quickly hack together a templating system for whatever website we're building. The system becomes very powerful when paired with a web server that can leverage fast tags in responding to HTTP requests. It becomes extraordinarily powerful when paired with a JavaScript library like htmx, allowing we to build fully interactive applications just from wer server rendered HTML.

Let's take a look at a simple example first

from fasthtml.common import *

app, router = fast_app()

# When the server gets a HTTP GET

# request, execute the function Index

# Return the output of that function

# as the body of the server's response

@app.get('/')

def Index():

return Div("Hello, world!")

serve()

When we run this program, it will spin up a web server on localhost:5001

curl localhost:5001

<!doctype html>

<html>

<head>

<title>FastHTML page</title>

<meta charset="utf-8">

<meta name="viewport" content="width=device-width, initial-scale=1, viewport-fit=cover">

<script src="https://unpkg.com/[email protected]/dist/htmx.min.js"></script>

<script src="https://cdn.jsdelivr.net/gh/answerdotai/[email protected]/fasthtml.js"></script>

<script src="https://cdn.jsdelivr.net/gh/answerdotai/surreal@main/surreal.js"></script>

<script src="https://cdn.jsdelivr.net/gh/gnat/css-scope-inline@main/script.js"></script>

<link rel="stylesheet" href="https://cdn.jsdelivr.net/npm/@picocss/pico@latest/css/pico.min.css">

<style>

:root {

--pico-font-size: 100%;

}

</style>

</head>

<body>

<div>Hello, world</div>

</body>

</html>

Great! Our body tag looks right, we have our hello world. One thing to note is that FastHTML includes a bunch of tags in the header that we don't necessarily want. By default, it includes:

htmxfor making interactive server side rendered appspico.cssfor nice default stylingsurreal.jsfor conveniences when writing other javascriptfasthtml.jsfor other defaults

Thankfully, these defaults can be disabled.

# ...

app, router = fast_app(default_hdrs=False)

# ...

curl localhost:5001

<!doctype html>

<html>

<head>

<title>FastHTML page</title>

</head>

<body>

<div>Hello, world</div>

</body>

</html>

Beautiful! A blank canvas.

Now, we can start building custom templates that take arguments.

def TitleSection(title: str, subtitle: str):

return Div(

H1(title),

H2(subtitle)

)

@app.get('/')

def Index():

return TitleSection(

title="In the Beginning...",

subtitle="A history of beginnings"

)

<!doctype html>

<html>

<head>

<title>FastHTML page</title>

</head>

<body>

<div>

<h1>In the Beginning...</h1>

<h2>A history of beginnings</h2>

</div>

</body>

</html>

One of the great features of FastHTML is that we can define any HTML tag attributes we normally would by leveraging Python keyword arguments. This means that we can create custom classes and modify the class of our HTML elements. Anything passed into a fast tag as a keyword argument will be rendered as an attribute on the HTML element.

Let's add some CSS to our HTML header, and style our elements.

app, router = fast_app(

default_hdrs=False,

hdrs=(

Style('''

.title {

font-size: 24px;

font-weight: bold;

}

.subtitle {

font-size: 18px;

color: #666;

}

'''),

)

)

def TitleSection(title: str, subtitle: str):

return Div(

H1(title, cls="title"),

H2(subtitle, cls="subtitle", data_custom="random custom attribute")

)

@app.get('/')

def Index():

return TitleSection(

title="In the Beginning...",

subtitle="A history of beginnings"

)

<!doctype html>

<html>

<head>

<title>FastHTML page</title>

<style>

.title {

font-size: 24px;

font-weight: bold;

}

.subtitle {

font-size: 18px;

color: #666;

}

</style>

</head>

<body>

<div>

<h1 class="title">In the Beginning...</h1>

<h2 data-custom="random custom attribute" class="subtitle">A history of beginnings</h2>

</div>

</body>

</html>

Notice the data-custom attribute on our h2 element!

FastHTML is simple, but ridiculously flexible. It's an engine that produces HTML in response to HTTP requests, and it does it really really well. FastHTML brings the functional templating style of JSX to Python.

Bringing in the Modern Web

Okay, generating HTML is useful, but modern web apps are much more than just handwritten HTML. If we're like me, when building a web app we want to use Tailwind and a component library. Let's explore how to make that work in our FastHTML application.

Integrating Tailwind

The easiest way to work with Tailwind in our project is to use the npm package, which means setting up an npm environment for our installation of @tailwindcss/cli. Docs for how to do this are easily accessible on Tailwind's website.

Once running the install command for npm, we need to do a few more things for setup:

- Create a

styles.cssfile in a folder calledcssin our project's root directory. In that file add an import for our application to use Tailwind.

@import "tailwindcss";

- Next, create a file called

Tailwind.config.jsfor configuring Tailwind. In this config, we ask Tailwind to scan our python files for Tailwind classes. One of the cool parts of Tailwind is that it doesn't necessarily need to operate on HTML. Tailwind relies on keyword matching, and some simple heuristics, to determine if the files it is scanning contain Tailwind classes.

module.exports = {

content: ['./**/*.py'],

theme: {

extend: {},

},

corePlugins: {

margin: true, // Explicitly enable margin utilities

},

plugins: [],

}

- Once Tailwind is configured, we can generate our initial compiled css file using Tailwind. In my project, I'm compiling it to a

styles.cssfile in anassetsfolder. In theassetsfolder I also store images/vector graphics. The below command will generate those styles.

npx @tailwindcss/cli -i ./css/styles.css -o ./assets/styles.css

- Finally, in our

main.py, we configure FastHTML to generate HTML which pulls in our generated css.

# ...

app, router = fast_app(

default_hdrs=False

hdrs=(

Link(rel='stylesheet', href="./assets/styles.css", type='text/css'),

)

)

# ...

Below is a rough outline of our new project file structure

website/

├── css

│ └── styles.css

├── assets

│ └── styles.css

├── main.py

├── package.json

└── tailwind.config.js

Leveraging Franken UI

Franken UI offers a fantastic collection of components that seamlessly work with Tailwind projects. Franken UI is great for FastHTML because it's designed from the ground up to work without any web frameworks.

Getting it set up in our project is very simple, just involves referencing some CDN documents in our HTML headers.

# ...

app, router = fast_app(

default_hdrs=False

hdrs=(

Link(rel='stylesheet', href="./assets/styles.css", type='text/css'),

Link(rel='stylesheet', href="https://unpkg.com/[email protected]/dist/css/core.min.css", type='text/css'),

Script(src="https://unpkg.com/[email protected]/dist/js/core.iife.js", type="module"),

Script(src="https://unpkg.com/[email protected]/dist/js/icon.iife.js", type="module"),

)

)

# ...

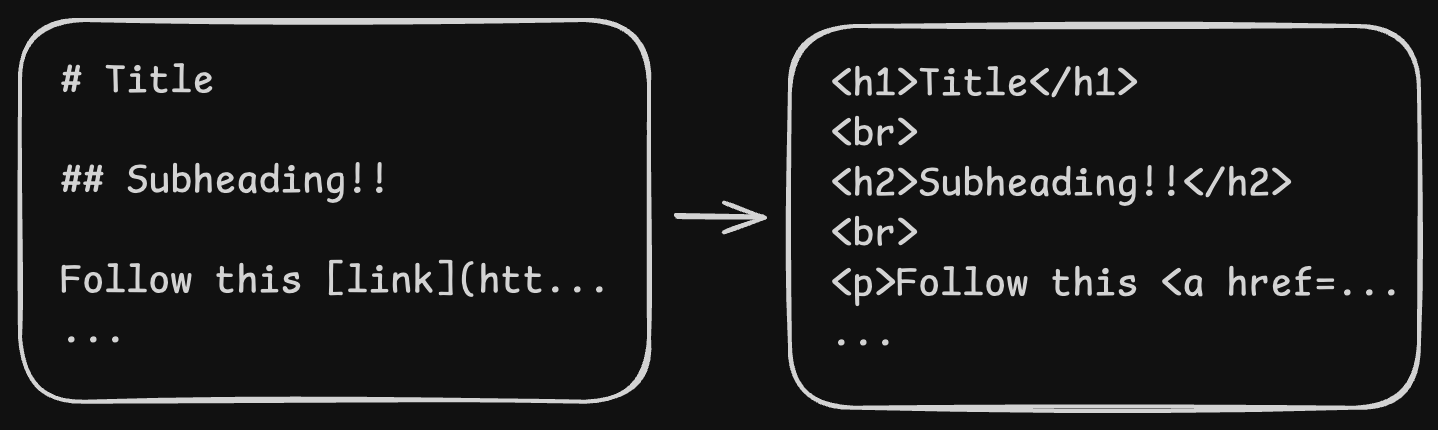

Writing articles in Markdown

Writing articles in markdown is much more convenient than writing them in HTML, mainly because there are a number of great graphical editors for markdown. To make markdown files work in our system, we need to take our markdown text, convert it into HTML, and configure our web server to serve it.

Here's how I handle it on this website at a high level:

- Markdown files are stored in a folder called

articles

articles

├── about.md

├── ai-copyright.md

├── engineer-solutions.md

├── fasthtml.md

├── fossora.md

├── lisp-machines.md

├── monads.md

├── professional-work.md

├── raft-kubernetes.md

├── search-engine.md

└── stargate-agi.md

- When the server starts, it looks in the articles folder, reads some

YAMLfrontmatter included in each markdown file, generates HTML, and stores each article as an in-memory object. - The server registers that HTML response to an endpoint corresponding to the article's filename (without the

.mdextension)

Implementation details

To parse markdown, and YAML frontmatter, I use the markdown and python-frontmatter packages.

Parsing and conversion is very straightforward

Here's the start of this article as markdown for reference.

---

title: How FastHTML Powers this Website

artist: tony etienne

hero: https://cdnb.artstation.com/p/assets/images/images/023/659/429/4k/tony-etienne-more-brains-in-jars-001.jpg?1579916139

artist-page: https://www.artstation.com/plongitudes

date: 2025-03-06

visible: true

tags:

- swe

---

[FastHTML](https://fastht.ml/) is probably one of the most exciting things happening...

And here's the startup code in main.py that parses and prepares all the articles. In the snippet below, I parse all the markdown files and create a bunch of article objects that have content (html), and url properties. These objects also have properties corresponding to each of the key value pairs defined in the frontmatter. This means they have properties like title, hero, etc.

article_names = os.listdir('articles')

md = markdown.Markdown()

articles = []

for article_name in article_names:

# ignores folders created on purpose/accidentally

# in the 'articles' folder

path = os.path.join('articles', article_name)

if os.path.isdir(path):

continue

with open(path, 'r') as article:

article = frontmatter.load(article)

article.content = md.convert(article.content)

article['url'] = article_name.split('.')[0]

articles.append(article)

Next, these articles are registered with the web server by pairing them with a FastHTML function for generating HTML based on that object.

def PostPage(article):

return Title(article['title']), Post(article)

def create_article_handler(article_obj):

def handler():

return PostPage(article_obj)

return handler

for article in articles:

app.get('/'+article['url'])(create_article_handler(article))

Why I'm Excited About this Architecture

Because all of the articles are stored as objects in memory, I can use that data to drive other parts of the site. The landing page for this site uses that list of articles to dynamically generate the grid of links. In the future, I could easily add other features for searching over articles, or dynamically generate pages that organize articles by tag. I can do all my writing in Obsidian, and the site will dynamically update itself to serve my new articles without manual intervention.

If we want to reference the nitty gritty of the internals of this site, this entire site is open source on my GitHub.